Image credit: Obstacleracingmedia.com

It started, quite honestly, with an off-the-wall idea, not the first one I’ve had with this longtime friend.

“We should do a Tough Mudder.”

Neither of us was in peak, or even great, physical shape, but one of us had done a few similar events, and the other had completed a half triathalon.

We both decided the Tough Mudder was a little bit scary, which, true to form, made it more appealing. We opted for the five-mile version, which seemed reasonable and still challenging.

Six months later, after countless runs, workouts, and videos watched, we joined thousands of others at a sprawling racetrack in central New Hampshire to test ourselves.

Neither of us knew what to expect.

I, certainly, never expected how much it would affect me.

TOUGH MUDDER

What transpired over the next several hours left a mark. Not only on my body, but on my outlook toward life and the challenges I face.

Some disclosure first.

It needs to be said upfront that Tough Mudder isn’t some benign social movement but, rather, a business and a marketing success story. It’s a physical manifestation of countless approaches to self-care that drive home the point that we have wildly untapped power within us.

I think it’s also fair to say it’s an escapist event for those with the privilege to indulge in it. The entry and assorted fees are not insignificant, more than a full day of work if you make minimum wage, and it’s well worth noting that within living memory, there was a time when something like it could not happen in our society. Countless people suffered—truly suffered, not the kind of suffering we experienced on the course—to allow all of us the privilege to participate together as one group. I don’t intend to make it seem, and it should not be implied, that the event is some social panacea, an afternoon of sweat that undoes everything else around us in this day and age. It isn’t.

And while Tough Mudder doesn’t particularly play up this particular angle, many other similar runs do focus on the military nature of their obstacles, implying subtly that it’s like going through the rigors of a warrior’s life. It isn’t that, either.

What it is, though, is truly amazing.

I cannot think of another lived experience that featured so much communal work and reward, with so many different types of people. Rarely in my daily life have I experienced so many slices of society as in the mud. It wasn’t a representative cross section of America by any means, but the Mudders I saw were a pretty eclectic group: young, old, all body types and abilities, and I presume a wide range of backgrounds, religions, political views and ideologies, working together toward a common goal of taking another step forward on the course, then another, to completion.

I expected pride in finishing. I didn’t expect pride in simply being there. The Mudder Oath, which we all took as a group, was a touchstone for a life well-lived: Help those who need it. Put others’ needs before your own. Don’t whine. Tackle the things you believe you can’t. Life is not a race toward the end, but a challenge to overcome your fears. Those fears will appear daunting and insurmountable and, often, when you have nothing left in you. No one can do it alone.

In the mud, like in life, little else matters but these ideas.

The course was painful, like life itself. Over obstacles higher than we thought we could scale, in disgusting muddy water up to our necks, with legs, lungs, hearts and muscle straining, we pulled each other through. No one asked who you voted for before lending a hand. No one pondered if the person next to them was worth their trouble; they were. No one forced or shamed us to help each other. Arms, legs, shoulders, bodies and words were freely offered to each other for support. My proudest moments were not when I overcame an obstacle—and I overcame every one with the group’s help—but when I helped others do the same.

It was a fantasy world, for sure. When we finished, we got our finisher t-shirt, headband, and beer, deservedly patted each other on the back, took some pictures, made some social posts, then got in our cars and drove back into our realities.

But if it’s a fantasy, it’s one I’d happily live in. It’s one I’m extremely proud to have finished. It’s one I will certainly indulge again. It’s one of the few moments in my adult life when I looked across a diverse crowd and felt…together.

In this vulgar, contentious day and age, it felt charmingly right.

A TRAGEDY

After a celebratory lunch outside of Boston, we returned to the parking lot where I’d left my car that morning, said goodbye, and made our respective ways home.

As I got on the highway, traffic stalled and then stopped almost immediately. A wall of lights flashed ahead. For a generally impatient person, traffic is frustrating. Add in mud, soreness and a long drive, and it’s over the top. I thought back to the Mudder Oath, and its “I will not whine. Kids whine.” provision.

The helicopter swooped down onto the blocked highway so quickly that it took a moment for the brain to process what was happening just yards ahead. This clearly wasn’t just a minor accident—the highway was now closed, in both directions. Car engines were turned off, windows rolled down, and slowly people opened their doors and got out onto the pavement.

We had nothing in common other than being stuck here, in a random spot on a random highway in a random town. Some left. A junky sedan and a luxury SUV were the first I saw to hit the grass and try to backtrack against stopped traffic to reach the previous exit. Perhaps someone was in labor. Perhaps someone just didn’t want to wait.

The rest of us talked and watched and, if they’re like me, pondered the costs of having one more bite at lunch, or one fewer joke with a friend, and being that person loaded onto the helicopter instead of a spectator, just by a sheer luck of timing.

The driver to my right railed on about aggressive drivers and did everything short of blaming the accident victim for society’s ills. To my left, a guy whom I learned worked in Manhattan talked weather with a young person with a Red Sox shirt and a neck tattoo. We marveled at how polite most people were…clearly those before us had let many emergency vehicles through, and there were now dirty looks given to the cars who set off on their own. Mostly, we looked on in awe at the fast and fluid motions of brave life-savers as they went about their business. The chopper loaded up, lifted off and soared over our heads. The conversations stopped, everyone returned to their cars, and we all set out on our myriad ways, rolling by a tangled heap of metal that had inadvertently and tragically brought together strangers.

THE ECLIPSE

If the Tough Mudder was togetherness by choice, and the tragedy was togetherness by random happenstance, the 2017 eclipse was togetherness in the context of our insignificance.

Astronomy is a humbling hobby. The vastness of the cosmos exceeds our tiny brains’ ability to ponder it. However, it can sometimes seem so removed from our life as to be disconnected. A supernova, for instance, one of the most powerful forces in nature, is merely a new and temporary dot in the sky. We can’t even see black holes. For most people, most of the time, astronomy is just something scientists study, nothing easily accessible to them in any dramatic fashion.

What I loved about the eclipse was that it was a stark reminder of the forces so much larger than ourselves or our species. We are, to quote Sagan, a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam. A small moon momentarily moved in front of a small star, and the most powerful nation that’s ever existed was darkened, humbled and awestruck.

Together, we looked up at forces that we couldn’t control if we tried.

Together, we saw our source of life blotted out.

Together, we shared our experiences and our awe.

And, if we chose to think about it, together we could see with very little effort how completely fleeting and meaningless our existence is, and incongruently, how important our choices are in the brief journey of life.

THE CHOICE

My point to these three stories is that, ultimately, we all have choices every time we act. We choose to be helpful, divisive or inward-focused. We choose our tribe, our actions and our fates. We can choose to acknowledge differences, brought about by our respective lived experiences that no one else can understand, or we can imagine others are governed purely by irrational thought. We can choose to be humbled by life, or not.

We all have different frameworks around our choices, those frameworks limit our choices, we don’t have an equal set of choices or frameworks, and sometimes there are no good choices. But there’s always a choice. Always.

You can choose to help or you can walk by. You can choose to wait for others or you can believe you are more important. You can choose to understand your own cosmic insignificance or you can think you are bigger than it all. You can choose to tackle your obstacles or you can not.

And we can choose to be together, with all the good and bad it brings. Or not.

In the lexicon of Tough Mudder, there are “No Excuses.” That day on the course, every step, every hurdle, I had to examine the excuses that popped into my mind and mentally move beyond them.

I’ve since been struck by how often I think about my excuses elsewhere, at work, in life, as I go about my day. Excuses are easy. They can easily drive my choices if I let them.

What are yours? And why?

And what’s our role together?

I did not know of Henry Worsley before last week, but it’s been difficult to get him out of my mind since. He died on January 24, just 30 miles short of his goal but after traversing more than 900 miles of Antarctica on foot, seeking to honor his inspiration, famed explorer Ernest Shackleton. Worsley was much more than an explorer, it turns out. He was a philanthropist, raising money for wounded soldiers. He was also himself a combat-decorated warrior, rising to the elite of the British special forces and spending a career on the knife’s edge.

I did not know of Henry Worsley before last week, but it’s been difficult to get him out of my mind since. He died on January 24, just 30 miles short of his goal but after traversing more than 900 miles of Antarctica on foot, seeking to honor his inspiration, famed explorer Ernest Shackleton. Worsley was much more than an explorer, it turns out. He was a philanthropist, raising money for wounded soldiers. He was also himself a combat-decorated warrior, rising to the elite of the British special forces and spending a career on the knife’s edge.

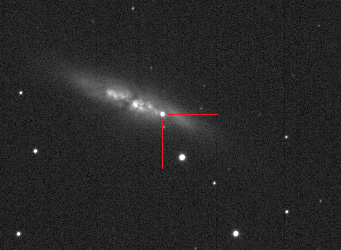

A star just exploded nearby, in one of the galaxies in our “Local Group.” It’s all relative, of course. The galaxy, M82, is about 11.5 million light years away, so the tiny dot that is the supernova is light that left M82 right around the time the Amazon River was forming, and long before people existed.

A star just exploded nearby, in one of the galaxies in our “Local Group.” It’s all relative, of course. The galaxy, M82, is about 11.5 million light years away, so the tiny dot that is the supernova is light that left M82 right around the time the Amazon River was forming, and long before people existed. Two of the three were easy: Comet ISON was definitely brighter than even a few days before and had a noticeable tail. Comet Lovejoy was incredibly bright but had no tail that I could make out. As Mercury and Saturn rose above the horizon, racing with the sun, I was hoping to see Comet Encke down near Mercury and make it 3-for-3, but couldn’t make it out. Still, it was my first time seeing two comets in one day, so that was noteworthy and quite cool.

Two of the three were easy: Comet ISON was definitely brighter than even a few days before and had a noticeable tail. Comet Lovejoy was incredibly bright but had no tail that I could make out. As Mercury and Saturn rose above the horizon, racing with the sun, I was hoping to see Comet Encke down near Mercury and make it 3-for-3, but couldn’t make it out. Still, it was my first time seeing two comets in one day, so that was noteworthy and quite cool.

On the 25th, Troop 45 held an astronomy observation session for those working on their merit badges. Scouts got to see Venus and its amazing partial phase, the International Space Station soar overhead, the Pleiades, Polaris, the Summer Triangle and much more.

On the 25th, Troop 45 held an astronomy observation session for those working on their merit badges. Scouts got to see Venus and its amazing partial phase, the International Space Station soar overhead, the Pleiades, Polaris, the Summer Triangle and much more.