There is something profoundly American about walking to a New England town green, handmade cardboard sign in hand. Something profoundly American about not walking alone.

That day, some people had warned of violence and damage; there had been enough the weekend before in America. Neither came to be. Just a crowd, much younger than me, perfectly within their rights of self-expression and mildly unruly.

Unruliness is as American as apple pie, bald eagles, and inequity. It is baked hard into our DNA as a feature, not a bug. The deeply flawed, brave, unruly (White) geniuses who committed to “hang together or, most assuredly, hang separately” on July 4, 1776, took on the world’s most powerful empire, could barely stand each other, fumbled greatly, and somehow won, creating this new kind of nation.

In the place of an oppressive monarchy, they put a republic weighted on the side of liberty and the individual citizen over the government, and then specifically oppressed anyone but White men. These unruly upstarts guaranteed a difficult life for our nation and horrors for its citizens.

Long may our government come second to its citizens.

Long may our growth require difficult times, for they create opportunities.

Long may we remain unruly. Long may we doubt actions to make us less so.

We lost some of that unruliness during the pandemic, perhaps out of justified fear of the virus, perhaps out of manipulation, perhaps out of growing softer, perhaps a combination. But we generally gave it away without a whimper, and that’s troubling, because power doesn’t go back in the genie’s bottle easily. You can see it manifested in China right now against Hong Kong or the Uighurs. You can see it in the actions by many here: left and right, elected, bureaucrat, and “expert,” wearing blue, a suit, a lab coat. You can see it in history, ours and humanity’s. You can see it kneeling on the neck of George Floyd for 8:46, hands in pockets, blankly looking at people screaming for decency. People and systems don’t give up power naturally, or consider they even have to.

Unruliness is important. Malcolm X described it as swinging instead of singing, standing instead of sitting. King said that cooling off was a luxury we can’t afford. Worthy of note that they were also two revolutionary men in the same struggle, and they hanged separately. Whites hanged them both, metaphorically, and many more, literally. To pull right from the powerful Kimberly Jones video that recently went viral, we are fortunate that Black America is looking for equality, not revenge. They’re not the only ones who are owed.

Slavery, civil rights violations, power struggles, and a forced, brutal inequity are not American inventions, nor exclusive to us or our history. But our ideals make them more painful, more of a scar. We need to be and do better toward those ideals. Progress, and I’d argue historically fast progress, is undeniable but it’s not enough. It never can be.

Because I post about politics so infrequently, some friends will be shocked I marched, or shocked to read all this. Aren’t I conservative? Oh, I sure am. Other friends will be shocked I marched, or shocked to read all this. Aren’t I liberal? Oh, I sure am.

I think for no one but me. Did I agree with everything expressed that protest night on the Southington Green, prior, or after? No, of course not. Do I always agree with parties or politicians I have voted for? No, of course not. Do you? I’m frightened if so.

I’m allowed to think for myself, the last I checked, although I do question that from time to time. It’s very likely I was the only person on the Green with a sign that spoke in terms of liberty. King said people like me “come to realize that their destiny is tied up with our destiny. And they have come to realize that their freedom is inextricably bound to our freedom.

We cannot walk alone.

I see no contradiction between the yings of “Molon Labe” and the yangs of belief that ”the arc of the moral universe is long, but it leads to justice. ”

I see no contradiction in having complex thoughts on complex issues. We shouldn’t fear that.

We do, though, partly because of how media and information is created and weaponized, and because it’s easy. The default.

We have to choose our buckets, I’m told. Have to strut our purity like peacocks to other people in our camp. Have to unleash an online mob on the enemy we don’t know and with whom we make no pretense of personal, actual dialogue. Shut up and comply, we’re told.

We will surely hang separately on this path. We already are.

I’m privileged in every way. Well-off. White. Male. Straight. Healthyish. Have every structural and personal advantage one could want, and so many that so many fellow Americans do not. I understand the feeling of unease at the world right now, at disruption, at change. A dear friend often shares a quote she likes: “When you’re privileged, equality feels like oppression. It’s not.”

Be unruly. Be uncomfortable. Speak face to face. Engage. Listen. Learn. Stand for a better America. Yours looks different than mine, and different from others’, and that’s OK. The marketplace of ideas should be open and free. Dialogue should be heated and uncomfortable. There should be a gut-level wariness of forced consensus, of the control of thought. Opposing views should be welcomed, considered, and debated. Your beliefs challenged. Orwell, who, with Huxley, could be the narrator of 2020, said it best. “If liberty means anything at all, it means the right to tell people things they do not want to hear.”

If they’re not violating another person’s natural rights, I’ll proudly stand by any American sharing in the mix of ideas, and hope we can give the oppressed ideas the greater benefit of doubt in that intellectual marketplace. The oppressed, dangerous, unruly ideas are the ones that move us forward. Always have. The oppressed, dangerous, unruly people are the ones who do it. Always have.

There will be pain in this process. Liberty is painful. Justice is painful. Freedom is painful. Honesty is painful. Knowledge is painful. It’s also the only hope for mankind, and the spark of it all drives me. I’m a proud, unapologetic patriot for the ideals of America, and part of that means an uncompromising look at how I have contributed to and benefited from our failure to reach them.

Don’t tread on me. Don’t tread on us. Those opposed to the principles of this nation see today as a period of American weakness. It’s not. They’ll seek to take advantage of it. They’ll lose.

But we cannot walk alone through it to make that so.

So, walk.

Happy Fourth of July.

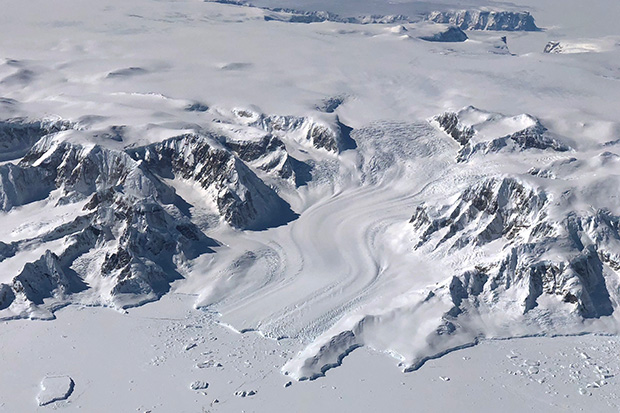

I did not know of Henry Worsley before last week, but it’s been difficult to get him out of my mind since. He died on January 24, just 30 miles short of his goal but after traversing more than 900 miles of Antarctica on foot, seeking to honor his inspiration, famed explorer Ernest Shackleton. Worsley was much more than an explorer, it turns out. He was a philanthropist, raising money for wounded soldiers. He was also himself a combat-decorated warrior, rising to the elite of the British special forces and spending a career on the knife’s edge.

I did not know of Henry Worsley before last week, but it’s been difficult to get him out of my mind since. He died on January 24, just 30 miles short of his goal but after traversing more than 900 miles of Antarctica on foot, seeking to honor his inspiration, famed explorer Ernest Shackleton. Worsley was much more than an explorer, it turns out. He was a philanthropist, raising money for wounded soldiers. He was also himself a combat-decorated warrior, rising to the elite of the British special forces and spending a career on the knife’s edge.

But what I saw in this group of 12- to 16-years olds was largely leadership. Like cooking dinner on a propane stove for their small groups, when it was snowing and their hands were cold and the wind was blowing. Or making sure that the group assumed responsibility for cleaning the site and leaving it better than we found it. How many politicians or CEOs would do that? Would they even call it leadership? Would they recognize it?

But what I saw in this group of 12- to 16-years olds was largely leadership. Like cooking dinner on a propane stove for their small groups, when it was snowing and their hands were cold and the wind was blowing. Or making sure that the group assumed responsibility for cleaning the site and leaving it better than we found it. How many politicians or CEOs would do that? Would they even call it leadership? Would they recognize it?